-

New Products

- EKG-6A

- MD05x

- Dolphi® pro

- Hand-held Multi-Gas Analyzer Ca

- EKG-3A Promoted Products

- Spirometer Type: P

- Sonovet ID

- C-Scan®

Contact Us

Pulse Oximetry for Veterinary

Pulse oximetry is a non invasive method of measuring the oxygen saturation of haemoglobin (SpO2) in arterial blood. It can thus be considered an indirect measure of tissue oxygen delivery, however, it is not a measure of patient ventilation.

It is used in both the initial screening and ongoing monitoring of patients to detect hypoxemia. It helps us to assess the patient’s response to therapy, and to detect any deteriorating trends in arterial oxygen saturation.

The pulse oximeter consists of a monitor and a light emitting probe.

Monitors – are available as either a small portable cage side monitor, or a larger multi-function machine.

Probes – the most commonly used probe is the two piece clip. One side of the clip has an LED that shines across the tissue bed to the second piece, which acts as a photo-detector. Clip probes may be used on any un-pigmented hairless skin, mucous membranes, ear pinna, nipple, vulva, prepuce, tongue or toe web.

Rectal probes are also available but not commonly used in Veterinary practice.

- Pulse oximeters may display false and inaccurate readings in the presence of the following:

- Patient movement (shivering, tremors, seizure)

- Poor perfusion (hypothermia, shock/hypovolaemia, vasoconstriction)

- Anemia

- Skin pigmentation

- Reduced localised perfusion (due to gradual tissue compression from probe)

- Very thin tissue (i.e. cat’s tongues and ear pinnae can be too thin for probes to measure accurately – a damp swab can be placed under the probe to increase width and compensate for thin tissue)

- Interference (visible light, electromagnetic energy, surgical diathermy)

- Abnormal haemoglobin – carbon monoxide (carboxyhaemoglobin) binds to haemoglobin with much greater affinity than oxygen. Pulse oximeters cannot distinguish between HbCO and HbO2 and will therefore display a falsely elevated reading. Hence, patients suspected of CO exposure should be evaluated using arterial blood gas, rather than pulse oximetry.

- Patients with normal lung function breathing ambient air should have SpO2 >94%.

- Patients with SpO2

Arterial blood gas analysis – is the gold standard method of directly assessing patient oxygenation and ventilation. In this instance, the parameter we are most concerned with is the partial pressure of oxygen (PaO2), where the PaO2 is a direct measure of oxygenation (and not ventilation).

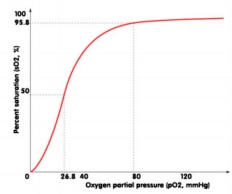

Where arterial blood gas measurement is unavailable, it is possible to extrapolate the patients probable PaO2 from SpO2 (or SaO2) using the oxygen-haemoglobin dissociation curve (see below). Before we do this, it is important to understand the significance of PaO2 in relation to the patient’s oxygenation status:

Normal PaO2 range = 80 – 100mmHg (in room air at sea level)

PaO2<80mmHg = Hypoxemia & supplemental oxygen should be provided

PaO2<60mmHg = Life threatening hypoxemia>immediate intervention required

PaO2<50mmHg = Cyanosis is now obvious due to deoxygenated haemoglobin = not compatible to life long term OHDC)

When evaluating the OHDC, we can see that normal hemoglobin is almost completely saturated (SpO2>94%) when the PaO2 is >80mmHg.

Note the s-shaped appearance, with a gradual plateau at the higher PaO2 levels (60-100mmHg). Throughout the plateau

section, misleadingly, small reductions in SpO2 are seen, corresponding with severe reductions in PaO2 – indicating a potentially severe hypoxemia (60-80mmHg). At the lower PaO2 levels (<60mmHg), the curve declines sharply, representing a rapid dissociation of oxygen from haemoglobin (and thus a rapid decline in SpO2).

Example: a patient with an SpO2 90% = PaO2 ~60mmHg = life threatening hypoxaemia

It can thus be said, that our patient’s SpO2 reading must be >94% for them to be oxygenating in the normal range of 80-100mmHg.

Oxygen Haemoglobin Dissociation Curve